June 30, 2018

The Adirondack Great Range

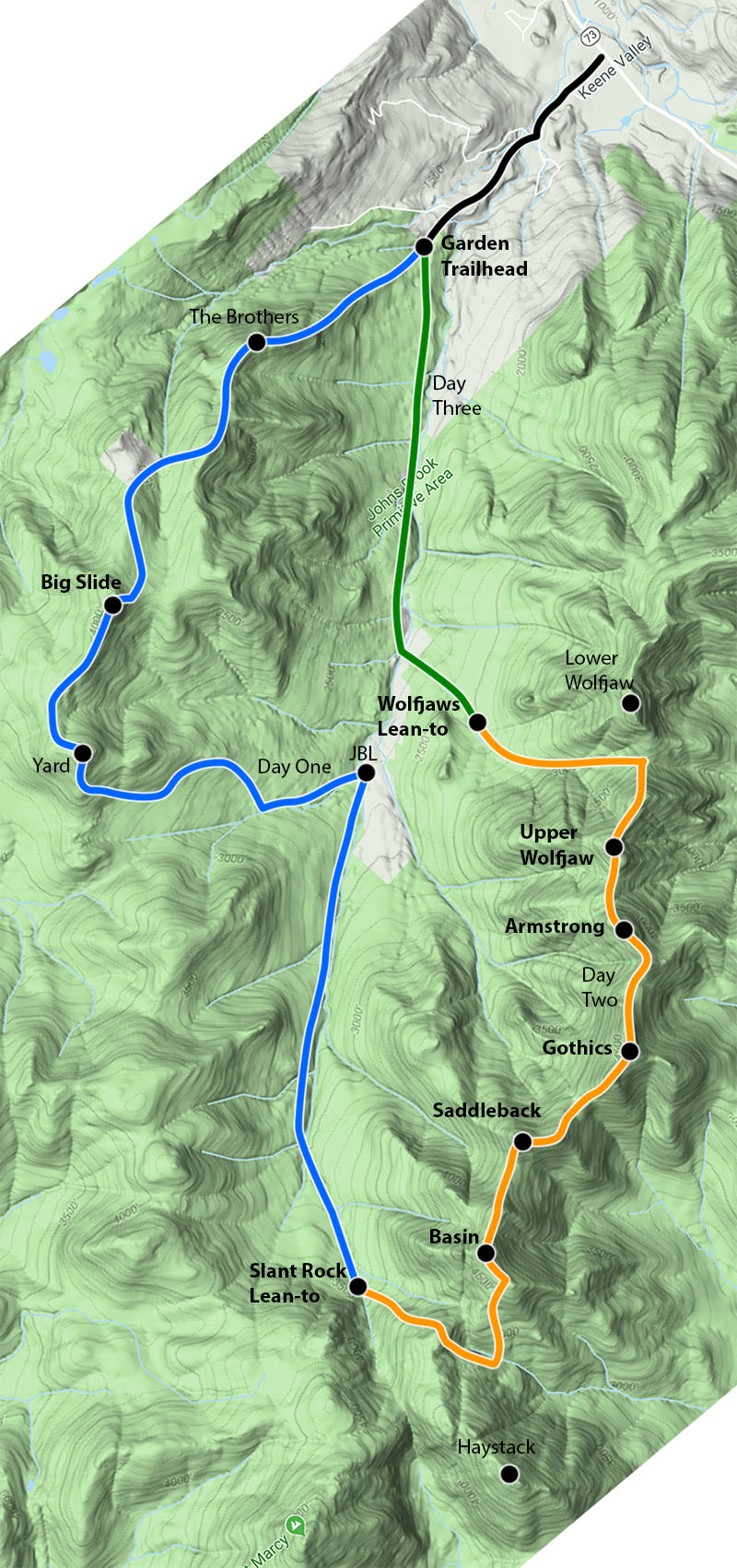

The “Great Range” spans a number of beloved high peaks in the central Adirondacks. The official definition of the range varies. But it typically includes Skylight, Marcy, Haystack, Basin, Saddleback, Gothics, Armstrong, and Upper and Lower Wolfjaw.

Having summited the first three on an earlier adventure, I aimed to traverse from Basin to Lower Wolfjaw that day. My trip began the day prior, with an ascent over Big Slide and Yard Mountains. That day ended at the Slant Rock lean-to, where I set up camp.

Shorey’s not-so-short cut

My Great Range day began with the annoyingly slow process of breakfast and breaking camp. I’m embarrassed to say this still takes me a solid 90 minutes or so.

But eventually, perhaps around 7 or 8 am, I was on the trail. I took a fork off the Phelps trail almost immediately onto Shorey’s Shortcut. Shorey’s Shortcut has gained a bit of infamy in this neck of the woods. Many say it’s not so much a helpful work-around for any particular itinerary but more of a giant, strenuous PUD (pointless up-and-down).

I don’t think that’s quite fair. In my current case (going from Slant Rock to Basin), this route was demonstrably shorter than going around past the Haystack spur. But it is indeed 700 vertical feet of tough scrambling upwards, followed by 300′ of scrambling downwards. You finish Shorey’s Shortcut higher above the valley and closer to your goal than when you started. But boy is there a lot of unnecessary ill will involved.

More Up

Your reward for all this effort? Another 700 feet of relentless up to Basin. This again involves scrambling over rocks and muddy rooty slopes, towards the ridgeline. It was a slow and strenuous beginning to a slow and strenuous day.

As if to add insult to injury, an exceptionally athletic man passed me by on the trail. He was a trail runner: seemingly a different species from us normal hikers. He was very tall and his long legs seemed to amble effortlessly over rock ledges and muddy slopes. No hands involved. I would like to point out I had 35 pounds of camping gear on my back. But this seemed downright superhuman.

Onto the Great Range with Basin Mountain (#13)

Soon I had gained the summit ridge. I had just a mostly-flat quarter-mile of hiking until the final summit push. I found the trail wet, muddy, and buggy. The dense boreal growth on either side made the air along the trail thick and stagnant. This was another theme of the day…muddy, hot, dank, boreal thicket. The Great Range during a heatwave in June!

And then I came to the summit out-cropping and all was forgiven. I stood at 4827’ feet above sea level, on the 9th tallest peak in the Adirondacks. There, I had commanding views of all the highest peaks: Marcy, Skylight, Haystack, Algonquin, and—way off in the distance—Whiteface. I felt a pleasant breeze, and the morning sun still sat far from its zenith. What a great start to the day!

Basin is a pretty underrated high peak. It doesn’t have the dramatic slides of Gothics visible from many vantage points. And its name seems pretty boring. Its summit sits deep in the wilderness—not at all easy to get to. And the peaks gets sandwiched between Haystack and Saddleback, along a ridgeline full of Adirondack Greatest Hits. Basin just never seems to command much attention.

But boy is the view from the summit great—you get to see all the other attention-grabbing peaks from a close vantage point. And as you make your way south along the range, you discover that its namesake basin is actually rather stunning to behold.

Notes on the Great Range

I ambled over a small sub-peak of Basin. Then I descended roughly 500′ into the col towards Saddleback. Muddy slopes and rock ledges meant this involved a lot of upper body action. Scrambling at its finest.

Traversing the Dix Range in October was a fun round-robin of peak after peak. They just seemed to come so easy. Sure, it was a long day, but entirely manageable.

The Great Range, in contrast, represents something else entirely. When you’re not climbing steep scrambles, you’re descending equally steep scrambles. And when you’re not doing either of those things, you’re in some swampy, and buggy thicket. Between scrambles I found myself negotiating deep pools of mud and hopping from rock to wobbly log to slippery root. Many years of heavy traffic have left the trail heavily eroded. Like many classic Adirondack ascents, it uses fall lines and streambeds, rather than switchbacks.

Adirondack miles come in all sorts of shapes and sizes. Lake Road and the Van Hoevenberg trail seem as easy as walking down a sidewalk. But the miles along the Great Range and slow and taxing. They demand your time, effort, and respect.

The Ledges of Saddleback (#14)

And then I came to it. The infamous ledges of Saddleback. I had heard the worst: a highly exposed scramble over large and somewhat featureless rock ledges.

I think the internets have overhyped this particular section of the trail. Yes, it’s a pretty intense scramble, and you’re high over the valley. But I never felt I was in a “one wrong move and I slide to my death” situation. And I get vertigo pretty easily.

I’ve also read people commenting on these ledges with remarks like “thank goodness I’m 6’2” or, “I’d never attempt that with a full pack”. For the record, I am 5’5, on a good day, and had a tent, filled bear canister, and 3.5 liters of water on my back. It was entirely manageable.

Having gained the last ledge, I paused to look back down at where I had come from. This was the first of two key moments that day when I felt glad I was doing the traverse west-to-east. If you do this in winter, please for the love of God, bring crampons.

I arrived at the summit of Saddleback, running into another solo hiker and three younger folks from Quebec. We would all leapfrog each other, along with a couple of other groups, that day.

Saddleback’s summit featured views nearly as spectacular as Basin. You’re not quite as up-close-and-personal with Haystack and Skylight and Marcy. But you get Basin’s dramatic southerly reliefs.

Gothics (#15) and the Cable Route

Then came another muddy ridgeline along the summit of saddleback. And then I popped up to the other high point of the “saddle.” After this, the trail dropped rapidly into the col between Saddleback and Gothics. I got a great view of the famed cable route up Gothics from here.

And then onto the cables! Here I honestly think the DEC is kind of messing around with people. Some of the steepest slab sections don’t have cables. And some of the less-scary parts do. Alas, I know not their logic.

That said, the cables proved helpful. I wasn’t quite fit enough to simply march up the smooth rock face grabbing the cable and pulling, step after step. But I did manage to march upwards in fits and starts. I stopped often to pant and sweat and catch my breath. Did I mention it was a heatwave? And I was carrying 35 lbs? Let the record show I’m not necessarily pathetic.

The cables were more or less a convenience feature heading uphill. But I could imagine them being a huge relief heading downhill. Thus the second point that day I was glad I was heading Northeast and not Southwest.

The summit of Gothics had a fine view. But it’s not nearly as exciting as the view looking at Gothics. Such is the tragedy of being one of the coolest mountains around.

Armstrong (#16)

A pressed on from Gothics, dropping off the summit ridge and towards Armstrong. Armstrong ranks as one of the least prominent official high peaks. It rises just 100 or so feet up from its “key col” with Gothics. That said the struggle was real. I was losing steam. I sat atop Armstrong, took off my boots, and gave myself a solid 20 minutes to just veg out and enjoy the breeze. A couple of other hikers soon followed suit.

Upper Wolfjaw (#17)

Then it was down and up to Upper Wolfjaw. Sadly this peak didn’t sport much of a view. Even sadder, it had a not-so-tiny secondary peak (honestly more prominent than Armstrong). Then came yet another steep, unrelenting, scramble down 600 vertical feet into the Wolfjaws col (Wolf-throat?).

The col formed a major intersection, with trails to both peaks as well as both the John’s Brook Valley and onto AMR land. My original plan involved dropping my pack and heading up Lower Wolf Jaw. But I had nearly exahusted my water supply, and I was nearly exhausted. So I decided to come back on a cool fall day to snag that one. Honestly, I should have just sat in the col for 30 minutes and gotten some sugar into my system. But I lacked the willpower and it was just so darn hot and humid. I fought the Great Range, and the Great Range won.

I descended 1000+ feet into the John’s Brook Valley, past a massive new slide that had opened up on the Wolfjaws after Hurricane Irene.

A restive night at the Wolfjaws lean-to

Then I came to the campsite at the Wolfjaws lean-to. The trio of young Quebecois campers had set up tents and were swimming in the nearby stream. An American couple had set up tents in the lean-to. Tens in a lean-to are technically not allowed. But it was pretty intensely buggy at this campsite, so I totally get it.

I pitched my tent near all these folks and began to decompress and make dinner. I had only traveled perhaps 6 or 7 miles that day, but that took a solid 11 hours and nearly all my energy.

That night was not so restful. The night before had been clear and crisp, at 3500 feet. But this night I was down below 2400 feet, and the air was moist and thick. The heatwave was at its zenith. I slept atop my sleeping bag, rather than in or under it. I light drizzle and intense mosquitos mean no cowboy camping. The tent was a heat trap.

To make matters worse, a couple arrived late in the night, headlamps blazing. They set up camp and their sleeping pads with the aid of a motorized air pump. The pump was somehow louder than any vacuum cleaner. Who does that!?

The next morning I hiked out the few easy miles from my lean-to to the Garden Parking lot. It was an intense few days with a lot of vertical but six solid high peaks were under my belt. And the views were pretty amazing. I left Lower Wolf Jaw for another day, but that wasn’t a huge deal. I kind of wanted to experience the Great Range—even a small portion of it—in better weather anyways.